NOSTALGIA: The closure of our railway lines

Dr Beeching, who had no professional experience of the railways, or even the transport industry, wielded a considerable axe – the “Beeching Axe” it has been subsequently called – to the industry. I have looked at a number of sources of information. None agree about the figures involved but, the Beeching Report recommended that something in excess of 2,300 railway stations were to be closed, 5,000 miles of track were to go and 70,000 railwaymen were to be made redundant.

The report had been commissioned by Ernest Marples’, Conservative Minister of Transport in Harold Macmillan’s Government. When it was published there was a public outcry led not only by the transport and railway unions but by the Labour Party which was then in opposition. However, after the General Election, when Labour replaced the Tories, they set about implementing the report with vigour.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe railways had been allowed to run down in the war years and, in the period of austerity after Germany’s defeat, there was little money spare for investment. As a consequence, the railways, which had been nationalised just after the War, were making an annual loss which reached £140m. in the 1960s.

There were other factors to consider and one was the growing adherence of the British public to the motor car. In the 1960s there were numerous British motor firms producing vehicles to suit almost all pockets and the Government, while undermining the railways, was effectively subsidising the motor industry by its huge road building programme.

If my memory serves me correct, it was the same Ernest Marples, just before he hired Dr Beeching, who opened Britain’s first motorway! This was, of course, the Preston Bypass, now part of the M6. The first person to use it was the Prime Minister, Mr Macmillan.

The report of 1963 did not recognise the railways for their potential to alleviate the traffic problems which, by that time, were clearly affecting some of our large cities. In 1970 I was a student at London University and was shocked to find that, often, people living in Muswell Hill had to park their cars up to five streets away from where they lived.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSince then we have all witnessed the destruction of our town centres, sacrificed to a newly-resurgent God – the God of the motor vehicle and the dual carriageway. It might have been so much better if Brigadier Lloyd, author of “The Potentialities of the British Railway System as a Reserve Road System” had caught the ear of politicians of the time.

What, though, was the effect, on Burnley and district, of the publication of the Beeching Report? The situation in 1963 should be put in context and the first thing to note is that there had been closures before that date. Perhaps the most significant was that Padiham station closed in 1957. Towneley station, on the Burnley to Todmorden line, had closed in December, 1952 and Reedley Hallows Halt in 1956.

There had been even earlier closures, the most significant of which was that of Cliviger in July 1930. This was joined, before the publication of the report, by the closures of stations at Cornholme, Portsmouth and Manchester Road, Burnley, all in 1961.

However, none of the actual lines in our area were closed before the publication of the Beeching Report. In the report there is reference to two local lines earmarked for closure. The first was the short stretch of track which served Barnoldswick, built by the Barnoldswick Railway Co. in 1871. It had, in part, been financed by Burnley businessman William “Billycock” Bracewell but was finally closed on September 27th, 1965.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe other reference to closure of track was to the North Lancashire Loop line which ran from Daisyfield, near Blackburn, through Great Harwood and Simonstone to Padiham, rejoining the East Lancashire line at Rosegrove. The line was effectively closed in 1964, though a short stretch remained open, to supply Padiham Power Station with coal, until 1993.

A number of points should be made about the Beeching Report itself. Its main intention was to close lines which were regarded as secondary routes. These, like the Barnoldswick and Padiham/Great Harwood lines, were often built much later and served much smaller rural communities than earlier lines which, generally, connected the larger cities and towns.

There was no intention to close more important lines and, the otherwise less significant ones that had important customers, (like the power station at Padiham) were to remain open. The line through Cliviger can be counted among these lines as it was occasionally used to transport materials for the great nuclear power station at Calder Hall, now known as Sellafield. This line was considered for closure but what happened was that, in 1965, it was closed to passenger traffic only.

The infrastructure on this line, sometimes called the Copy Pit line, remained intact but there was a significant closure on the line because the “west spur”, at Hallroyd in Todmorden, was cut depriving Burnley of a direct line to Manchester. The west spur is better known as the Todmorden Loop and, as you will know, there has recently been some good news about it in that the Government has found the funds to relay and reopen the connection. In the 1980s the line through the Cliviger Gorge was reopened to passengers when building society workers from Burnley, when their society was taken over, accepted jobs in Bradford.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt is not generally realised these days but Burnley once had three rail routes into Manchester. As indicated, the most direct was the line through Todmorden which closed to passengers in 1965 and then partially reopened. The one through Accrington, Blackburn and Bolton to Manchester has remained open though, as we shall see, the track at the eastern end was eventually taken up.

The third line ran from Burnley to Accrington where, at the station itself, a line from Manchester, Bury and Baxenden Bank joined the track. It was this line which was used by the old Colne to London direct train. It came out of Manchester to the south via Stockport and it took over six hours to get to the capital. The section from Accrington to Bury was one of those proposed for closure by Dr Beeching.

Incidentally, Dr Beeching also proposed the closure of the Bacup, Rawtenstall, Bury to Manchester line but, when this came to pass, it gave local enthusiasts the chance for the development of the present East Lancashire Steam Railway, a splendid attraction for the whole area.

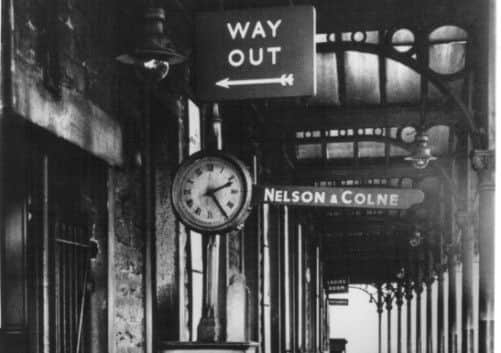

This leaves us to mention the most talked about of the closures which were a direct consequence of Dr Beeching’s recommendations. He listed, for closure, the former Leeds & Bradford Extension Railway which had opened in 1848. The line refers to the track beyond Colne, through Earby and Thornton-in-Craven, to Skipton, which, I think, was finally closed in 1970.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI had always assumed this line was built by the same firm which had constructed the Blackburn to Burnley line but this was not the case. Those who know more about railways than myself, have told me the merest glance at the buildings constructed by the L&B indicated, when they were in situ, that they were different. All I remember is that, on one occasion, travelling from Preston to Nelson, when I was in my teens, I contrived to fall asleep only to wake up in Skipton – with no train coming back to Nelson until the next morning! This must have been a family thing as it also happened (on more than one occasion!) to my father though he got on the train in Blackburn and intended to alight in Burnley!

A final aspect of this story is that, with Dr Beeching, steam locomotives were finally put out to grass. There were no steam passenger services in the Burnley area after 1965 and, three years later, the Rosegrove railway workshops were finally closed. This was particularly sad because, to some extent, Rosegrove had been a mini railway town, a mini Swindon, which had the effect of making the place just that bit distinctive. It is something I miss – and I have not lived there!

The Beeching effect can be seen all around Britain. It is easy, now, to say he was much too vigorous in his closure programme and cutting the less important lines had the effect of reducing users of the more important ones. On the other hand, perhaps he realised the dominance of the train would pass with the Age of Steam.

What he could not have known is the present popularity of the train in our bigger cities and towns. I wonder what he would have thought about spending £30 billion on a new West Coast line? What would he think about all the charming volunteer run steam railways that live on after him?

Roget Frost